Decisions are hard.

There’s a reason why Barack Obama never picked out his clothes in the morning while he was in office.

Making a decision costs mental energy and like all our mental resources, that energy is finite. Once this energy reserve is depleted, our decisions become a lot worse. That’s why Chess players play worse matches in the afternoon than in the morning. They have less resources left to make good decisions.

What’s more, some decisions seem impossible to make. How do you decide if there’s no airtight case for either side?

It’s a dilemma that’s all too familiar to me.

But maybe there’s an answer, a shortcut to help us use less energy on decisions and to decide in those vague moments where both options seem equally balanced.

I’m calling this trick BDM – baseline decision making. Here’s how it works:

Decisions under uncertainty

In law, there are two truths: the actual truth and the one you can prove.

When in law school, you mostly deal with the first kind of truth. You have all the facts of a case and need to apply the law to solve it correctly. But life rarely gives you all the facts, so after university, things get a bit more tricky. All of the sudden, there are two sides to each case and each person alleges something else.

Often, it’s possible to prove one side wrong so that the situation is like in law school. You have all the facts and can apply the law. But sometimes, there’s just no telling who is right and who is wrong. How do you decide then?

In these situations, the law has it’s own sort of Baseline Decision Making.

- In criminal law, a non liquet (= the facts are not clear) leads to acquittal.

- In civil law, the person bringing the claim often loses, unless there’s some unique situation that reverses the court’s Baseline Decision Making.

- And in very time sensitive situations, where no real clearance can occur, the decision might be solemnly based on who stands more to lose from a wrong decision.

In other words, even in situations of uncertainty, the law will find a clear decision. It might not be the right one at all times, but given our knowledge of the consequences of a wrong decision, it’s acceptable to take that risk to come to a decision at all.

Learning from the Law

How can we apply this concept of Baseline Decision Making to our own life?

Well, let’s first take a look at how we often approach decisions. We either

- make an in-the-moment decision based on our gut feeling or “intuition”

- aim for a rational, thought-based process based on the pros and cons at hand

Both decisions require us to expend mental energy, regardless of whether we pick our morning outfit spontaneously or after thorough contemplation.

And while both forms of decision making have their place, they also have certain drawbacks:

- our intuition is formed by past experiences, so it tends to reinforce the same behaviour over and over again

- pros and cons list often lead into a dead end if we’re not able to actually quantify both sides

Plus, again, making a decision costs mental energy and depending on when we make that decision, we’re more likely to make a wrong one (that’s why binge snacking is more likely to happen at night than during the early morning: you have less energy available to make sound decisions).

The alternative?

Baseline Decision Making: spend that energy upfront and apply it to many decisions. It’s like leverage for your brain. Or like picking your go-to date look. Think once, decide twice.

How does it work?

Let’s take an easy example: I get offered an opportunity in my professional life, maybe a speech at a conference about GTD or to write an article for a paper summarising my favourite study techniques. It’s not quite clear what the benefits would be. It could advance my career a bit or maybe not. It’s definitely more work. What should I do?

- I could make a gut decision based on how the opportunity feels in the moment.

- I could try to quantify the benefits and tradeoffs of going to the conference versus spending that time differently

- I could make a Baseline Decision regarding career related opportunities

Baseline Decision Making: it’s really a line

Now when it comes to making our upfront decision, it can seem daunting. After all, how am I supposed to know exactly, what sort of decision I should be making?

I often can’t even decide after knowing the details. How am I supposed to decide before?

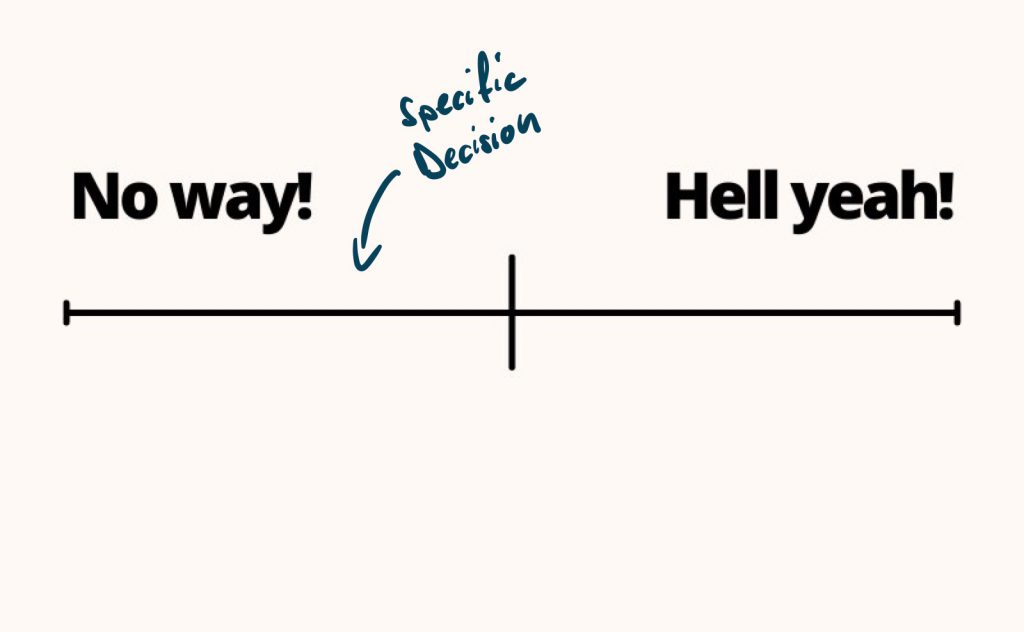

Here, I’ll try to apply a second trick. Instead of thinking of the decision as a pure yes or no, it’s helpful to envision it as a line:

Now, I don’t know exactly where the future decision falls. And even in the moment, it’s often impossible to actually quantify the pros and cons and say: well looks like we got a score of +7 for yes.

But I could look at my situation as a whole and decide: should I be looking out for opportunities to advance and diversify my career right now? Or is it the time to really double down on one goal and eliminate all distractions?

Baseline Decision Making: which side of the spectrum?

In my example, this would depend on a few factors:

- do I even have one clear goal to double down on? If not, saying yes to new opportunities is a great way to actually discover such a goal

- am I early on in my career or more seasoned? Am I in the middle of it or can I see the end? Early on and towards the end, branching out and exploring different options makes more sense than during the middle part where I should try to get really good at the one thing I’m doing (this concept is called the Career Martini).

- am I generally a person who commits to a thousand things but has trouble finishing them? Or am I someone who is very much set in their path and could profit from a new experience here and there?

Depending on how I answer these questions, I’ll know on which side of the spectrum I should fall in general.

Again, there’s no way to really quantify things. But I know that unless I find very specific and convincing arguments as to why this situation requires a different approach, my Baseline Decision Making is clear.

And that’s all that’s left. Asking myself whether this is actually a very atypical situation – or not. And while it’s hard to quantify where exactly a decision should fall on our line, it’s much easier to estimate whether it’s a “normal” case or an outlier.